Bayard & Holmes

~ Jay Holmes

On August 26, 2015, the Philippine government took a major step in Philippine foreign policy toward its closest ally, the US.

During an official visit to the Philippines, the commander of US Pacific Command, Admiral Harry Harris, met with Philippine Defense Secretary Voltaire Gazmin. During that meeting, Secretary Gazmin requested US military assistance in resupplying Philippine military forces in the West Philippine Sea, or, as China calls it, the South China Sea.

Though largely ignored by most Western media outlets, that request is a signal event in US-Philippine relations.

Those of us who remember that the US military was unable to settle workable continued lease terms for two huge major US bases in the Philippines in 1992 might have to subdue an automatic “we told you so” response. Harris is a smart man, and he gave no such smug response. Instead, he politely listened and agreed to pass the request up the chain of command.

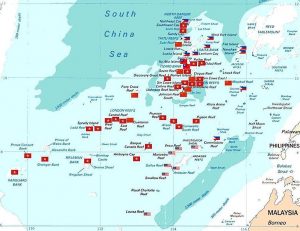

The Spratly Islands, which lie between Viet Nam and the main Philippine islands, are germane to this request.

The islands are under conflicting claims between the Philippines, Viet Nam, Malaysia, Taiwan, China, and Brunei. Since the largest of the Spratlys, Taiping Island, is only 110 acres at best, depending on the tide, it is clear that the land in the Spratlys is not what is central to the competing claims. Even the fishing rights, oil, and natural gas deposits are not what really drive the claims.

The critical underlying issue is the effect that a successful territorial claim would have in defining the national boundaries of China and the other claimant nations, and how those boundaries would impact navigation through what has previously been considered international waters.

The Philippines’ request for military assistance from the US is, on the surface, simple enough. However, beneath the surface, there has been a lack of unity on several issues that have greatly impacted US-Philippine relations since the fortunate demise of Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

The standard view of the fall of Marcos and the rise of Corazon Aquino in 1986 holds that the Marcos regime ended, Aquino brought democracy, the new democracy evicted the US from Subic Bay Naval Base and Clark Field Air Force Base, and everyone lived happily ever after. The reality was, and remains, somewhat more complex.

Marcos died, but the Marcos regime did not quite die with him.

The pressure for the US to abandon its bases in the Philippines did not come from a populist groundswell of Filipino public opinion, as was assumed by most Western journalists. Many on the right assumed that the US would, and should, remain. Many working class Filipinos also had no desire to see the US gather up its cash and leave. In fact, according to Philippine research, 85% of the Philippine people viewed the US favorably then, and still do today. Principally, wealthy landowners and the senators that they owned drove the desire for the US to leave. They saw the US as having enabled the fall of Marcos and the eventual rise of Corazon Aquino, a land reformer, to the presidency in 1986.

One of the central themes in Corazon Aquino’s campaign was land reform, which was not a welcome concept to the wealthy plantation owners.

In 1972, her husband, Senator Benigno Aquino, was arrested and imprisoned on various charges after he spoke out against the Marcos regime. In 1980, after Benigno Aquino suffered a heart attack in prison, Imelda Marcos, likely in part due to US pressure, arranged for him and his family to travel to the US for medical treatment and asylum. The Marcos regime and the wealthy landowners that supported it hoped that they had seen the last of the troublesome Aquino family. They hadn’t.

In 1983, Marcos was hospitalized for a kidney transplant, and reformers sensed change in the wind. Aquino, well aware of the danger that awaited him, returned home to the Philippines, intending to battle the Marcos regime from prison by way of grass roots public support. He thought it would work. Unfortunately for Aquino, Marcos thought it would work, too.

When Aquino stepped off the plane, security forces ushered him toward a waiting van. He was shot in the back of the head, and he died before reaching the hospital. Marcos and his pals had allowed a hapless communist agent to slip past the massive security scheme, and he may or may not have fired the .357 magnum revolver that killed Aquino. He may have simply been placed in the right location to be framed for the murder. The communist agent was shot dead at the scene, too, so we can’t ask his opinion.

Statue of Benigno Aquino, Jr.

in Conception, Tarlac.

Image by Ramon F Valasquez,

CC3 License, wikimedia commons.

The murder of Aquino backfired on the Marcos gang.

Benigno Aquino became a martyr for the people of the Philippines. Aquino’s funeral on August 31, 1983, started at 9:00 a.m. at Santo Domingo Church with the Cardinal Archbishop of Manila, Jaime Sin, conducting the mass. It ended at 9 p.m., when Aquino was buried at the Manila Memorial Park. More than two million people lined the streets during the procession, which was broadcast by the Catholic Church-controlled Radio Veritas. The state controlled media did not broadcast the funeral. Eventually, after Corazon Aquino became president in 1986, twenty-four members of the Philippine military were convicted for conspiring to murder Senator Benigno Aquino.

Most of the long-awaited fairytale democracy has yet to materialize in the Philippines, but democracy has survived, land reform did occur, and now here we are in 2015, fielding a request from the Philippine government for military assistance. And who occupies the office of president of the Philippines now? Benigno Aquino III, the son of the late Senator Benigno Aquino II.

So, what does that request for US military assistance mean in real terms?

It means that in 2015, the Philippines live too close to China. It also means the Philippines has not yet fielded a credible military force to prevent Communist China from moving its border to within two hundred miles of its shores. At this point, even the pissed off ex-landowners are thinking that the US Navy, backed up by a US Air Force, operating from US funded non-US bases in the Philippines could make life easier in the South China/West Philippine Sea.

To state this simply and accurately, the country of the Philippines is requesting that the US play the role of the colonial protectorate in guarding Philippine transport through the Spratly Islands. The Philippines is asking the US to risk military confrontation with China on its behalf.

What’s in it for the US?

The primary advantage is keeping international maritime traffic open through the region. It is not in the US interest for China to expand its Exclusive Economic Zone and its border to the eastern edge of the Spratly Islands. Another advantage is that, if the US must ever resort to a conflict with China, the alliance with the Philippines has the potential to extend the US perimeter to the Spratlys, helping to keep the fight away from our shores.

And how will the US respond to the request?

Cautiously, and quietly . . . We have been waiting for that request for a few years now, and nobody in the Pentagon or the State Department was surprised by it. The preference thus far has been to encourage the Philippines to start building a credible Navy and Air Force. That might happen one day, but not soon enough.

Lots of plans have been announced, but five years into their planned grand naval expansion, the Philippines has yet to acquire a functioning frigate to send to the Spratlys. Their new fifty meter patrol craft are not going to scare the Chinese. I cannot read the mind of President Obama or his closest advisors, but I don’t imagine that the White House would be anxious to commit to another military escalation while heading into a campaign season. A slogan such as “More Wars for Your Enjoyment” isn’t going to win any elections.

My best guess is that the US will step up diplomatic efforts to encourage closer military ties between the Philippines and all its neighbors not named “China.”

In the meantime, China is now dealing with economic problems and complex domestic political intrigues, and it is not as rock-solidly prepared as it would like us to believe to escalate beyond harassment and intimidation in the Spratlys. China will take everything it can get by way of intimidation, but I don’t see it significantly escalating its aggression in the Spratly Islands in the near future.

Various agencies and businesses here in WA State are gearing-up for the PRC President’s visit. It will be interesting to see if anything constructive comes as a result.